Guest Dose from Jim Chandler introduced by his son, The Kid

Kid: Tonight’s dose is a tune that I’ve actually sung to some of you. Moose, Captain–two mosquito nets in a cabana on a Thai island come to mind. I would never have learned it were it not for my Pops (subjunctive?), and it is a song to which he has devoted some thought:

JC: I bought my 45’s from a place called Casino Amusements in the town where I grew up, Asbury Park, NJ. It was a warehouse along the Jersey Central railroad tracks, a monument to mid-century America, filled with jukeboxes and cigarette machines.

What these shiny appliances had in common was that both had to be resupplied regularly, a service Casino Amusements duly provided.

In a dusty office in one corner of the warehouse, on a counter striped w cigarette burns, there would be a small stack of 45s that had been recently liberated from a jukebox.

One could purchase these for 20 cents, at a time when they’d run you 89 at the five and dime.

The rate of obsolescence of any given 45 could be measured by how soon it appeared in that 20-cent stack.

Out of these purchases I built a library of 45s that became the envy of my friends.

My relation to the orchestrated cycles of rising and falling fortunes in the pop music industry may have been somewhat altered by the fact that I was making his actual purchases of records sometime *after* their removal from the jukebox, which lagged behind their fall from the charts.

This frugal system also meant that I would not have a record to play until after it had fallen into relative obscurity.

Unlike now, if the radio wasn’t playing your song, then you literally could not hear it, unless of course you purchased it at Casino Amusements.

The Drifters was a group for whom many songwriting teams at the legendary Brill Building generated successful material. “It was the dream of many songwriters during the early 1960s to write for the Drifters,” writes Ken Emerson in his dense history of these writers, Magic in the Air–including the teams of Carole King and Gerry Goffin, and Burt Bacharach and Hal David.

The Drifters’ role here is remarkable for the dramatic changes in personnel that the group underwent in the late 1950s and early 1960s. Popular within the world of mid-fifties R & B, the original Drifters lost their talented lead singer Clyde McPhatter to the military draft in 1956 but carried on for two years, partly with songs from Jerry Lieber and Mike Stoller, two Jewish songwriters at the center of the Brill Story, who arrived with the Coasters a couple years earlier.

In 1958 their manager George Treadwell (who managed Sarah Vaughan) fired the whole group after a poor showing at the Apollo Theater in Harlem and replaced them with The Five Crowns, led by Ben E. King.

King himself left the group after two years, and the position of lead singer would have to be filled again twice during the group’s early-60s heyday with “On the Roof,” “Under the Boardwalk,” and “On Broadway.”

After months of touring, the first major recording project undertaken by these new Drifters was “There Goes My Baby” in March, 1959, and the resulting record, as it happens, was also the very first purchase I made at Casino Amusements, a little before my twelfth birthday.

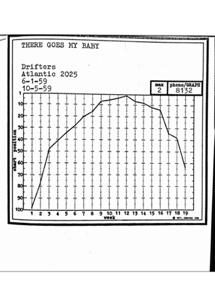

Here is the chart of its impressively long run on the Billboard Top 100 in 1959:

Unquestionably the pivotal moment for the Drifters story, the release of this song, co-written by two teams who had previously not been associated with the Drifters at all, also marked the beginning of a refashioned R & B sound that would dominate the period.

The redoubtable deejay and historian Marv Goldberg calls it “the song that was to change the sound of Rock and Roll music.”

Ben E. King himself had drafted an early version of it, but it was revised and produced in the Brill Building by Lieber and Stoller. (Both Treadwell and The Five Crowns’ former manager also claimed a writing credit.)

The song’s strangeness derives in part from two decisions made by Lieber and Stoller.

The first was to add strings. The second was to avail themselves of timpani that happened to be in the recording studio to supply a booming baion beat that lends the song the feel of a Latin recessional march. Buddy Holly had experimented with strings the year before, and so had an R & B group called The Orioles.

But There Goes My Baby marked a new departure for strings in an R & B song. Nor was the borrowing of a baion beat original with this song, for Lieber and Stoller apparently found it in a 1952 Sylvana Morgana song-and-dance number in an Italian film of 1952.

https://youtu.be/j-HNZLg6ntI

The transformations wrought to forge this recording brought short-term success to all concerned, but more tellingly, the song became a point of departure for future Drifters releases and much other Brill Building-associated music for several years to come.

Henceforth, strings would feature in the crossover music of performers such as Chuck Jackson (who worked very much in the tracks of Ben E. King), Sam Cooke, The Shirelles, The Crystals, and Mary Wells. The baion beat caught on almost immediately, and spread so quickly that it eventually became the subject of its own song—”The Baion Rhythm”—composed by Goffin and recorded by the lead singer of The Skyliners.

Its adoption, moreover, opened the door to further Latin influences that shaped both The Drifters later music and the music it influenced, such as Ben E. King’s “Spanish Harlem,” (written by Phil Spector, with help from Lieber). Another Brill Building songwriter, Mort Shuman, would describe himself as someone “who wrote rock ‘n’ roll but lived, ate, drank and breathed Latino.”

There Goes My Baby was a record with which I developed a real intimacy in its own time, and in retrospect I think it did much to shape my musical predilections.

The Drifters-influenced crossover sound, which anticipates much of what came to be called soul later in the 1960s, would be decisive for my preadolescent taste in ways I came to find troubling.

Fifteen years ago I stumbled on a CD of Chuck Jackson’s greatest hits in a music store and immediately popped it into my car’s player so that a friend could listen to it.

But even my favorite of his recordings: “Any Day Now” suddenly struck me as vaguely appalling? What is going on with all those strings, I asked myself, and why is it that I never noticed them before?

In spite of some (modest) musical training, and serious early exposure to jazz and some classical music by my uncles, my musical appreciation seemed to be grounded absolute schlock.

It was only later that I realized that “Any Day Now” was actually written by Burt Bacharach, and that he wrote it in the Brill Building under the tutelage of Lieber and Stoller.

Another salient feature of the early Top 40 system is the tender age of the youths it reached and catered to.

Indeed, at eleven one could actually feel like an elder statesman of this music in some contexts.Earlier in 1959, on a Saturday in mid-February, my younger sister’s eighth birthday party fell on the weekend after Buddy Holly, along with the Big Bopper and Ritchie Valens, died in a plane crash (February 3, 1959).

When I looked in on the party, I saw a group of seven- and eight-year old girls huddled around a thick-spindled 45 player, weeping over Valens’s then #1 song: Donna.

Valens’ death gave Donna, as well as La Bamba, on the flip side, a longer run on the charts than most, which is to say a few months.

This little domestic scene dramatizes the extraordinary power of a cultural and technological conjuncture: a big psychic investment on the part of the very young, coupled with the rapid vicissitudes of novelty and obsolescence in the production cycle.

My own capture by The Drifters’ sound dramatized how larger musical formations took shape in relatively brief time in such a culture.

For better or for worse, the New York Sound, performed by African Americans and shaped by songwriters committed to “Jewish Latin” was my sound, and it formed the building blocks of time out of which my pre-and early-adolescent experience was constructed.

For those of us in the grip of this constellation of technology, format, and media, personal experience was measured in staggered temporal segments with great power to shape feeling and memory.

Our sense of life history, of history itself, was powerfully conditioned in such circumstances, and given periodical articulation in the bargain.